Work accessibility into your content strategy

Because the modern web offers us an unprecedented level of access to information and interaction through audio and visual media – becoming both an integral part of the overall experience and an important method of delivering content to the end-user – what can we do to help people with disabilities enjoy an equivalent experience?

Without question the most effective way of making this kind of content accessible to the widest audience – including those with disabilities – is through the provision of text-based alternatives. Why? Because information rendered in electronic text can be easily enlarged for people with low vision, spoken aloud so that it’s easier for people with reading disabilities to understand, or rendered in whatever tactile form best meets the needs of a user.

So what are some of the text-based options available to us for different types of audio and visual content? What could we be doing? What should we be doing?

Audio-video content

Live video broadcasts

Any video content on the web that isn’t described in text poses a potential barrier for people with disabilities. So by providing a descriptive label (Level A: to achieve minimum level of accessibility) of the live video content’s purpose you can ensure that, even if access cannot be achieved, a user can at least determine what the non-text content is.

This is really easy to do and it makes such a difference. Don’t forget, it’s more than likely that while planning this content someone, somewhere will have written a more than adequate description anyway. Bash it into shape, tidy it up, and use it.

For UK residents the BBC News website offers a 24-hour live video feed of its rolling news channel (Figure 1). They provide a very brief description of the channel, ways that you can contribute, as well as a polite reminder that you’ll still need a TV licence to stream the feed.

Figure 1 - Live stream of the BBC News channel

Another option might be to offer captioning (Level AA: enhanced level of accessibility) as an alternative to the live audio track. This will enable people who are deaf or hard of hearing to watch real-time audio-visual content. Captioning not only includes dialogue, but also identifies who is speaking and other notate sound effects that affect comprehension.

What’s that? Am I seriously suggesting you go to such lengths as to hire an out-of-work court reporter to relay the dialogue of your live webcast or seminar? I think it largely depends on your audience and the nature of your broadcast.

If you’re, let’s say, a college or university offering a series of live video lectures to your students then it’s more than likely there’s a policy of some kind requiring accessibility of online instructional material (or something to that effect). Whereas if you’re a small start-up conducting a one-off live webcast, presuming you’ve make it clear from the outset that real-time captions are not being supplied, providing everyone with a descriptive label, which introduces the host(s) and lists the topics you’re aiming to cover, will suffice. If you then have plans to publish the webcast in its recorded form at a later date then look at providing captions or a full transcript of the dialogue.

Prerecorded video

Aha. Now everything has been recorded and cut to your exact requirements suddenly providing a text alternative like captioning (Level A) doesn’t seem quite so daunting a prospect does it? You won’t have to worry about the perils of live broadcasting, or whether there’d have been enough time to cross-check the captions for spelling, style, or even legal pitfalls.

Depending on how the content is presented to the user not all prerecorded video requires captioning. The W3C’s WCAG 2.0 recommendations state that:

Captions are provided for all prerecorded audio content in synchronized media, except when the media is a media alternative for text and is clearly labelled as such.

What they mean by a media alternative is content that presents no more information than is already presented in text.

Take this recorded interview on Cricinfo.com (Figure 2), because they’ve offered a clear choice of either watching or reading the interview via a text transcript (Level A) no captions were required. But if the video content had offered a different take to what is represented in text form then they would have needed to provide captions. That’s clear enough.

Figure 2 - Prerecorded interview on Cricinfo.com with full transcript

It’s likely some clients will have concerns about the effect that providing a text alternative to prerecorded video will have on the speed of the publishing process. The way I look at it is this: if you’ve missed the live version of your favourite radio show you know and expect there’ll be a short wait for the recorded version to be cut and uploaded to the web. I don’t believe there’s anything wrong with providing captions or a text transcript at a later date. Just make it clear where and when a text alternative will be available.

There are some excellent resources available for online captioning and since March YouTube have offered an automatic captioning feature for all English language videos. I’m led to believe that a clear audio track can produce some very impressive results. Hats off to them I say.

Now, to paraphrase Napoleon’s revision to the Seven Commandments in George Orwell’s Animal Farm: some alternatives for non-text content offer a more equivalent experience than others. Captions, while an unquestionably important way of providing people who are deaf or hard of hearing with an equivalent experience of prerecorded video content, don’t offer quite the same level of immersion and understanding that an on-screen interpreter can provide for those fluent in a sign language (Level AAA: additional accessibility enhancement). Again, choosing this route depends on your audience, location, policies, and resources.

Audio-only content

Live audio broadcasts

Similar to the challenges posed by broadcasting live video, the use of a descriptive label (Level A) ensures that, even if a user cannot access the live audio-only content, its purpose is clear.

A good demonstration of an effective description for a live audio feeds is the BBC’s iPlayer (Figure 3). They provide the user with helpful information such as the names and time slots of the incumbent and following presenters and a brief description of today’s show.

Figure 3 - Live audio stream of BBC 6 Music on iPlayer

Prerecorded audio

For a person who is deaf or with a mild to moderate hearing impairment text transcripts (Level A) are relied upon for comprehension of prerecorded audio-only content. Furthermore, individuals with visual and auditory perceptual disabilities, including dyslexia, may also benefit from getting information through more than one source at the same time.

Offering more than just a blow-by-blow record of who said what during a sound recording, a text transcript should also contain descriptions of significant sounds and key actions that take place – say if someone produces a mobile phone from their pocket to demonstrate a new ringtone or a door slams shut.

A good example of a text transcript can also be found at Cricinfo.com. Their Cricinfo Talk podcast (Figure 4) is available to play through the website, but they’ve also provided a full transcript of the dialogue.

Figure 4 - Prerecorded audio on Cricinfo.com with full transcript

Again, the thought of having to produce a text transcript for every new piece of audio-only content may concern some clients. But there are services out there that can help you publish good quality text transcripts if you lack the in-house resources or time. If you’ve used a script to create the prerecorded audio content then there really is no excuse. It’ll give you a great starting point and need only require a few corrections for it to closely reflect the actual recording.

Charts and graphs

For a blind or low vision user the information contained in a chart or graph may be difficult or impossible to comprehend without a text alternative.

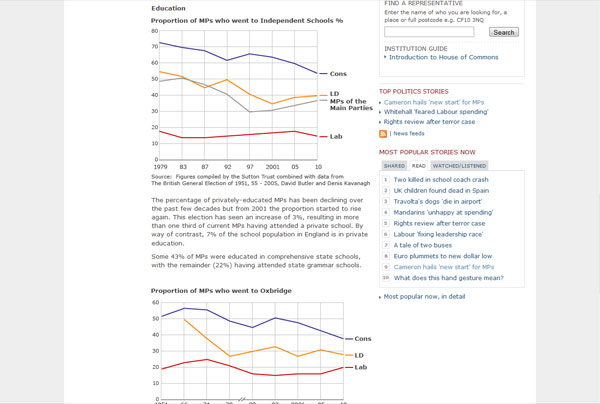

What form the text alternative takes depends on how the chart and graph has been presented. If one or more have been used to supplement an article, which outlines or explains the data contained within, then that can serve as the text alternative (Figure 5).

Figure 5 - BBC News article using supplementary graphics

But sometimes the text needed to serve the same purpose and present the same information as the chart or graph is too lengthy, or there is limited space. In this instance a hidden or external long description (Level A) can provide the user with helpful information on the type of chart used and a detailed summary of the data, trends, and implications. And, where possible and practical, the actual data is provided in tabular form.

Hiding it can mean linking to a separate page by way of the longdesc attribute within the img tag, but there are CSS positioning tricks you can use to effectively shift the long description from view, but for anyone viewing the page using a text-only browser or having it relayed via a screen reader this information would be visible.

A little daunted? A content strategy can help…

I believe that to stand the best chance of successfully introducing and adopting the processes, technology, and techniques required to provide an increased level of accessibility to our users, we have to take responsibility for the way our web content is planned, created, delivered, and governed. That means assimilating accessibility into a web content strategy.

Because it’s all about breaking our content down into the smallest re-purposeful chunks, for use across a whole host of different mediums and technologies, consider how much easier a web content strategy would make providing text alternatives for non-text content? It’ll allow audio and visual content to be rendered in a variety of ways by a variety of assistive technologies.

It’s also about getting everyone who interacts with web content (surely everyone now, right?) on board. Your technical team may need to make changes to the way content is published so that assistive technologies can recognise it and react to it. Your workflow may need to be altered to reflect the production of text-based alternatives. Your page templates may need to be revised to accommodate further content. All that and more is considered part of the strategy.

So what now? Do you conduct an audit to find out what existing content you could provide text alternatives for? Would a more sensible plan be to start from this point forward? It depends, but you can’t go too far wrong by prioritising. Before you ask how much non-text content already exists you have to ask how much of it is considered integral to the key tasks performed on the website? If that 60 second video demonstration of your web application in action plays an important part in selling its benefits then I believe, regardless of how long it’s been present on the website, you should look to offer a text-based alternative.

Why should I or my clients care about accessibility?

It goes beyond nobility. Whether it’s buying what you sell, making a donation, or simply getting in touch, creating content that is accessible to people with disabilities will allow more people the opportunity to interact, enjoy, and be stimulated by your web presence.

And as the general population in developed nations ages, and with it an increase in the number of people with functional limitations, it is essential that the traditional and existing resources that are being replaced by the web – from submitting a VAT Return to checking your bank balance – are effective, efficient and satisfying for all.

Sources and resources

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0

- WebAIM’s WCAG 2.0 Checklist

- Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI)

- Web Accessibility: Web Standards and Regulatory Compliance

Pingback: Tweets that mention Work accessibility into your content strategy | Richard Ingram | Shut the door on your way out Cicero… -- Topsy.com

Pingback: NASA, Content Strategies and Statistics « Peter Ganza's Blog

Pingback: Are Downloadable Audio Books Better Than Cassettes or Compact Discs? | Download Zone

Pingback: Brukskvalitet » Blog Archive » 10 gode grunner til å gi avslag på publiseringsønsker

Richard

I loved your diagram at the top and have taken it from Flickr to use on a blog post of my own.

Thanks for sharing it.

Rebecca

Thanks Rebecca. Be sure to provide a link to your blog post when it’s up as I’d love to read it.

Pingback: A whole stack of content strategy links | Firehead

Pingback: The Epic List of Content Strategy Resources | Puck @ Your Local Heroes

Pingback: The Biggest List of Content Strategy Resources, Ever |merchee makes it easy for non-developers to accept credit cards and charge for recurring subscriptions - merchee makes it easy for non-developers to accept credit cards and charge for recurring subscri