Content lessons from our distant past

When we consider how much of our world’s rich and varied history has been lovingly and painstakingly recorded you’d think by now we’d have more than enough material with which to run a pretty tight ship; and yet still we remain as arrogant, fickle, and naïve a race as those who roamed, ruled, fought, loved, lived, and died before. We still brazenly, blindly, and bewilderingly stagger into periods of deep economic hardship; utterly convinced that things would turn out differently this time. We still, in search of fertile lands, dare to place and grow large settlements beside the earth’s active fault lines and volcanoes and inside floodplains waiting for appalling and brutal acts of nature. And we’re still, it seems, intent on imposing our – otherwise credible, peaceful, and thoughtful – customs, politics, or beliefs on unsuspecting and unmoved populations.

Sometime around 1046 BC – depending on what material you read or hold dear – the powerful Shang Dynasty, who had presided over ancient China for over five hundred years, were toppled by their western Zhou neighbours. The act of conquering this established, prosperous kingdom was indeed a fine achievement by the Zhou, but what is most curious and interesting is the strategy they devised to govern this vast land. Much like the Kush who, roughly at the same time, were themselves also embarking on a similarly impressive foray into, and eventual conquest of, ancient Egyptian territories, the Zhou knew that rather than immediately installing their own brand of religious, moral and ethical doctrine they had to heed to a more popular, and stable, tune: the status quo. Besides, anything they didn’t like the sound of could have been slowly adapted when the dust had long since settled.

I believe that, even in the distinctly less volatile world of content management, this remains an important lesson. The same way you cannot just overthrow an old system of government and traditions without first looking at how many of those traditions defined their people and kept them in check, you shouldn’t be in such a huge rush to disregard and haul out that rotten, slow, and one-dimensional CMS without first finding out the reasons why, from the people that use it day in day out, how it came to be so. While no-one can question your motivation and fevered intention to usher in this brave new dawn try not to be in such a tremendous rush.

It goes without saying that the smaller the organisation, lavish the budget, or determined the mood is to blow the winds of change, the more likely you’ll be able to make bigger and quicker strides in the execution of your long term strategy – though, in all likelihood, to expect a wholesale denouncement of what has gone before with regards to content production and management is, perhaps, rather too optimistic to expect. But no matter, start small. Concentrate your efforts on one particular area of content production where your voice holds most weight and show the rest how it could, and should, be done. Make a statement by taping reams of A4 sheets together and daubing countless boxes and arrows showing each role and their responsibilities to illustrate just how long and convoluted a single task in the content production process is around here. Look for opportunities to run some authoring tasks simultaneously to cut down on costs. Calculate how much time your department – or someone else’s, if you’re feeling particular shallow that morning – wastes by re-writing or -packaging existing content for essentially the same audience.

Make a fuss. Make some noise. Make yourself a bloody nuisance. But if, or when, you have the jurisdiction to make such bold, sweeping changes remember that evolution rather than revolution offered the Zhou the best chance of providing the economic and spiritual stability needed for a long and prosperous rule. And rule they did: right up until around 256 BC.

Sources

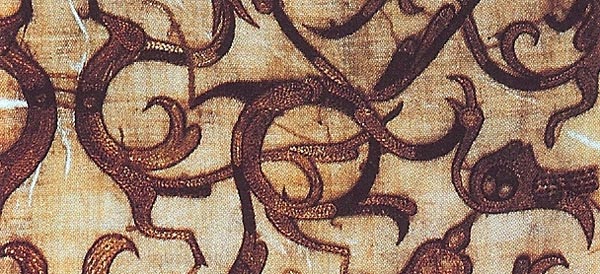

- A History of the World in 100 Objects – Episode 23

- Managing Enterprise Content, Ann Rockley, New Riders 2003

Pingback: Tweets that mention Content lessons from our distant past | Richard Ingram | Shut the door on your way out, Cicero… -- Topsy.com